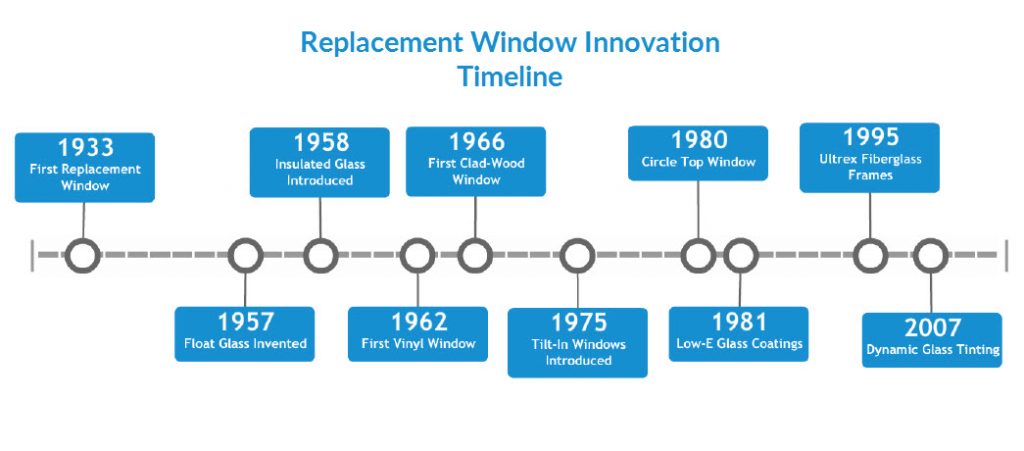

Marvin Windows Top 10 Window Replacement Innovations

Windows have changed a lot in the past 100 years. Here are 10 innovation benchmarks on that timeline.

How often do you think about the windows in your home? And how often do you consider the technology behind your windows? For past 100 years window technology has evolved significantly and each development shifted the sands completely disrupted the manufacturing, construction materials, and energy efficiency of windows for both new construction and remodeling. Here are ten innovations that revolutionized windows and, with them, the design of today’s structures and the lives of the people who live, work, and play in them.

1950s: Float Glass

Alastair Pilkington, technical director of British glass manufacturer Pilkington Brothers, claimed to get the idea for Float Glass while watching a dinner plate floating in the sink. His brain child was a method of floating molten glass over a bath of molten tin, an approach that by the late 1950s was producing flatter and more uniform glass than had ever been possible. This breakthrough was an important step down the path to today’s energy-efficient windows, as the higher-quality glass made possible the application of window films. Float glass is now used in all windows.

1950s: Insulating Glass

Although insulated glass was patented as far back as 1865 actual products only appeared in the 1950s under the name Thermopane. The first versions consisted of two panes welded together at the edges with a ¼ inch dry air space between them—like the double glass liner of a Thermos bottle. By the late ’60s welded insulating glass was in half of all windows. When manufacturers widened the space to a better-insulating ½ inch, however, expansion and contraction put too much stress on the weld, so the industry moved to steel or rubber spacers that bonded to the glass with sealants that could absorb the movement. By 2007 about 90 percent of all windows had insulating glazing.

1960s: Vinyl Windows

Although German window manufacturer Trocal introduced the first commercially viable vinyl windows in the 1950s, the technology first appeared in the U.S. in 1964, when Thermal Industries began offering a vinyl unit to the replacement window market. Vinyl windows didn’t become a player in the new construction market until the late 1980s, but growth since then has been rapid. By 2009 they accounted for about 60 percent of all window sales.

Late 1960s: Clad Windows

The late 1960s saw an entirely new window category called clad windows. Andersen introduced its Perma-Shield vinyl clad window in 1966; Pella followed four years later with and aluminum clad product. Marvin was the first to offer a standard aluminum clad finish on its entire product line. Clad windows combine the look of a traditional wood on the inside with a weather-proof exterior that never needs painting. This low-maintenance feature has made them extremely popular: by 2003, about 93 percent of the 25 million wood window units sold in the U.S. market were being made with either an aluminum or vinyl cladding.

1970s: Tilt-In Replacements

The first all-vinyl, double-hung tilt replacement window for the U.S. market was introduced by Pittsburgh, Penn.-based Polytex in the mid-’70s. Newer products, such as Marvin’s Tilt Pac Double Hung Sash Replacement System, are cost-effective options for upgrading an older double-hung window with a frame that’s in good condition, but with a sash or hardware that needs replacement.

1980s: Round Top Windows

Round Top windows had traditionally been hand-crafted by small millwork shops. Around 1980, market demand created the incentive for Marvin to develop manufacturing for round top windows. A Marvin engineer in R&D with experience in boat building applied his knowledge of building curved, wooden frames to develop effective manufacturing processes for the Round Top window. The availability of round top windows not only served historic replacement needs, but literally changed the face of modern home design.

1980s: Low-E Glass and Gas-Filled IGUs

A low-E coating is a thin layer of transparent metal that slows heat transfer through the glass. In winter, it reflects some heat back into the room, while in summer it reflects heat from the sun back out. The first commercially available low-E product was Southwall Technologies’ Heat Mirror film, released in 1981 with the help of Lawrence Berkley National Labs and a $700,000 Department of Energy R&D grant. The original product was a suspended film. Although suspended films are still available, manufacturers eventually perfected the technology to deposit the coating on the glass, an approach that’s less costly and more common. By 2005, low-E coatings were on 56 percent of all windows.

While low-E coatings lowers radiant heat loss through the window, filling the air space in an insulated glass unit with a low-conductivity gas reduces convective losses. The most common and cost-effective gas fill is argon, which is 34 percent less conductive than air, although some super-high-efficient windows use more expensive an less conductive krypton gas. Krypton needs a smaller air space than argon (3/8 inch versus ½ inch), so it’s use in triple-pane windows lets the manufacturer make the glass unit slightly thinner.

1990s: Impact Glass

After Hurricane Andrew blew through South Florida in 1992, officials blamed much of the $25 billion in damage on winds that pressurized homes and blew them apart from the inside. Impact windows were developed as a way to keep wind out of the building. Also called Hurricane windows, they’re subject to strict testing requirements, including the ability to withstand a hit from a 9-pound 2×4 shot out of a cannon at 34 mph, as well as 9,000 cycles of positive and negative pressurization. They achieve this via a combination of laminated glass (as in a car window) and heavy-duty hardware. Building codes are requiring these in hurricane-prone coastal zones, as well as inland areas subject to tornadoes.

Mid-1990s: Ultrex Frames

Despite the popularity and rot-resistance of vinyl windows, they’re not particularly strong, and can expand and contract with changes in temperatures, putting stress on window seals. The mid-1990s saw the introduction of window frames made from composite materials like Marvin’s Ultrex, a fiberglass material. It’ stronger than vinyl, wood or aluminum, expands and contract less with changes in temperature, and has a vastly superior ability to block heat transfer. For instance Ultrex frames have three times the strength of wood and eight times that of vinyl.

2000s: Dynamic Glass

The state of the art in window technology is dynamic, or switchable glass. Two versions are currently available. Electrochromic windows control solar gain via a transparent conductor placed between the glass panes that be gradually darkened or lightened using an electric current. The glass blocks heat gain, but remains transparent. The window can be manually tinted or controlled by an automation system. It should not be confused with privacy glass, which uses liquid crystal technology to switch from clear to opaque, and has no energy-saving function.

It’s exciting to think where we might be going next with window design. There’s no doubt these changes have generated significant energy savings and comfort for homeowners across all climate zones.

To learn more about Marvin Windows, visit us at www.WrightwayBuilt.com. We have proudly served homeowners in the Appleton, Fond du Lac, Oshkosh, and the surrounding areas since 1977.